The Landworkers’ Alliance is a union of farmers, growers, foresters and land-based workers.

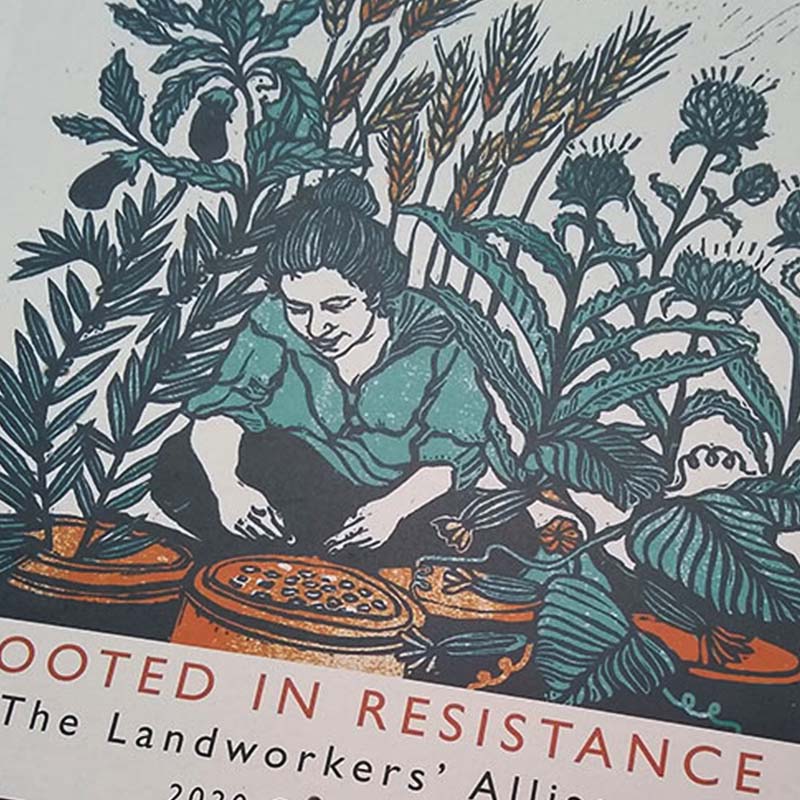

The Landworkers’ Alliance’s 2020 calendar was entitled Rooted in Resistance.

Bringing inspiring contemporary stories of powerful campaigning, organising, and land rights defence around the globe, sparking hope at this time of deep instability..

The stories were brought to life once again alongside 12 beautiful, original lino cuts by Rosanna Morris – which were this time printed in a beautiful colour palette of teal and orange.

From the migrant worker solidarity of Italy’s USB union, to the women’s village of Jinwar, Northern Syria – Each story depicts a movement or community working to build not only a better agricultural or land-rights system, but also a fairer society – each in their own way, and with their own tactics.

Inside the Rooted in Resistance calendar:

February: Jinwar, the Women’s Village – Building a new world in the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria

It started with a piece of land.Houses built with red clay earth, willing hands and ancient methods, building a bridge between our history and our future.Before that – it started with the belief that women, together, could find ways of living, a balance of human and nature, a society free from patriarchy, a new horizon to reach for. But even before that it started with a people who fought for freedom, who took the decision to defend themselves and their land, and build something better. This is how it always starts.

Jinwar is a story of many beginnings.

It is a village in Rojava in which women and children live collectively, building a community based on women’s liberation and democracy. While the self defence forces of Rojava fought against the forces of Islamic State, the women’s movement began sowing the seeds of the world that would grow from the ruins of the old. In place of the brutal patriarchy and fascism of ISIS, the new society being built in Rojava – the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria – is based on democracy, diversity, women’s liberation and ecology. Jinwar is a powerful example of how the values and vision of the movement can be brought to life in a way that has inspired countless people in the region and around the world.

The Kurdish, Arabic and Yezidi women who live in the village participate in a communal economy, taking shifts at the village bakery, store and agricultural works and receiving a portion of the village income. Each home, which is built using traditional methods of clay-brick building, has a kitchen and a garden, and there is a central kitchen and shared gardens which are used as a collective resource. Women choose to move to Jinwar for a range of reasons – some have been widowed, other are escaping difficult domestic situations, others are simply compelled by the vision of a communal, ecological life centred around women.

Jinwar is a place of learning and knowledge, hosting an academy and a centre for natural health. Daily life is also a learning experience, as women learn how to perform tasks traditionally done by men, such as driving the tractor. Together, the women and children living in Jinwar are answering the question posed by the Rojava Revolution: How to live?

March: Indigenous land defenders on the frontlines – Berta Cáceres

‘In our worldviews, we are beings who come from the Earth, from the water and from corn. The Lenca people are ancestral guardians of the rivers who teach us that giving our lives in various ways for the protection of the rivers is giving our lives for the well-being of humanity and of this planet.’ Berta Cáceres‘

The Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) was founded in 1993 by the renowned indigenous leader and environmental activist Berta Cáceres. COPINH is a powerful self-organised grassroots movement dedicated to the defense of the indigenous Lenca people and the environment in the Intibucá region of Honduras. It advocates for indigenous rights and the protection of commons such as water and land, and organises against the privatisation of resources by foreign companies and investors, which COPINH calls the ‘recolonization of our country’.

Between 2006 to 2016, COPINH, under the leadership of Berta Cáceres, coordinated a sustained and successful grassroots campaign against Sinohydro, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), and Honduran company Desarrollos Energéticos (DESA), After years of struggle and ongoing resistance from the local indegenous Lenca people, the companies were forced to pull out of building the Agua Zarca Dam at the Gualcarque River in Intibucá, western Honduras. The Gualcarque River is sacred to the Lenca, who depend on the river and its ecology for their subsistence.

The resistance and protests against the dam were met with sustained violent repression, detention and torture, and several leaders of the struggle were murdered during this time. After years of threats and attempts on her life, on March 3rd 2016, Berta Cáceres, was assassinated in her home – an attack that shocks-waves throughout the world. There is an ongoing legal investigation into who ordered the murder.

For many years La Via Campesina and international human rights organisations including Global Witness have been investigating and documenting abuses and violations against social justice organisers, environmental activists and land rights defenders. Their monitoring shows that people standing up to the governments and companies that steal their land and harm the environment are being targeted across the world. The most recent figures for 2017 shows that over 200 land defenders were murdered, and in 2018 the number was 150. The majority of these murders are linked to mining, hydropower, agribusiness and logging projects. On the frontlines of fighting climate chaos, protecting ecosystems and safeguarding human rights, every defender comes from a community and an ecology that they risk their lives to protect.

June: Sowing seeds of resistance : the fight for food sovereignty in Palestine

In Palestine, the struggle for food sovereignty is inextricably intertwined with the Isreali occupation. By seizing land and severely restricting access to essential resources such as water, harvests, markets and freedom of movement, a core strategy of the occupation has been to forcefully separate the Palestinian people from their land-based identity steeped in traditional practices of farming, food and culture.

In the face of the constant attacks of the occupation and the increasing challenges of climate chaos, a forefront of the resistance are Palestinian farmers. Through movements such as the Union of Agricultural Work Committees and the Palestinian Peasants Movement, farmers are organising for food sovereingty by defending their lands and keeping alive Palestinian agricultural heritage.

There are also land-based grassroots projects emerging across Palestine, including the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library which was founded by Vivien Sansour in 2014. Based in the West Bank at Beit Sahur and Battir, the initative works to find, collect, reproduce and distribute seed varieties that are no longer widely grown in order to cultivate the knowledge of traditional Palestinian farming practices and food cultures.

The Seed Library started when Vivien began to realise how many local fruits and vegetables such as the Jadu’l Watermelon that were familiar to her as a child were disappearing or had already disappeared. For Vivien, like many Palestinians, losing these varieties, tastes and memories meant losing part of her culture and her identity.

The work of the Seed Library is about much more than rediscovering and reviving Palestinain heirloom varieties that have almost disappeared, it’s about preserving and keeping alive the ancesteral heritiage, cultural histories and rituals, and the stories of autonomoy and resistance in Palestinian agriculture that are contained within the linegages of these seeds.

In this context, traditional Palestinian heritage and heirloom seeds are an important root of resistance, providing both an active link to the culture and identity that surrounds certain foods and crops, but also a strategy to increase crop resilience and food soveriengty in the face of climate chaos and the deprivation of essential resources.

As Vivien says “Farmers who can produce their own food and make their own seeds represent a threat to any hegemonic power that wants to control a people. If we are autonomous, we really have a lot more space to revel, to create our own systems, to be more subversive.”